Iranian.com

by Ari Siletz

22-Sep-2011

In 2010 James Dolan, chief executive officer of Cablevision got paid about $13 million, or about 400 time the wages of an ordinary you and me. By comparison the manager of the royal household of the Achaemenid king Darius the Great was paid 700 sheep, 600 loads of flour, and 32000 liters of beer and wine. This is about 100 times the wage of an ordinary Achaemenid postal worker (courier). Never mind how much Darius got paid—the king was a national symbol, and therefore beyond labor pricing--but when it comes to income disparity Achaemenids seem to have the U.S. beaten four to one in terms of social justice. How do we know how much workers and top administrators got paid during the Achaemenids?

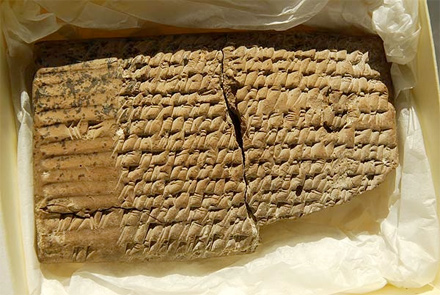

The information comes from deciphering a fraction of the 12000+ clay tablet “file cabinet” found at Persepolis circa 1930, and now stored mostly in the U.S. These are the famous Persepolis tablets now facing death by lawsuit in the U.S. legal system. The U.S. says the IRI is a state sponsor of terrorism and therefore U.S. citizens can sue Iran for injury resulting from IRI sponsored terrorist activity. For example, if Hamas hurts an American citizen during a terrorist attack, the injured person can sue Iran for supporting Hamas’ act. In fact many plaintiffs have already won large damages against Iran; the only problem was how to collect the court awarded money. After some hunting around in law books, they found out that a loophole in the 2002 Terrorism Risk Insurance Act (TRIA) allows them to auction off the Persepolis tablets housed in U.S. universities. That should raise a few million, they thought.

But just last week the NIAC news email brought good tidings that some of the tablets have been rescued, apparently through clever use of a legal technicality. Lawyers defending the tablets in Massachusetts successfully argued that the plaintiffs couldn’t prove that the items actually belong to the IRI. To get more detail on the temporarily good news I talked on the phone with NIAC president Trita Parsi. NIAC has been involved in the tablet rescue efforts, leading where it can and assisting where it can. When I asked what would happen to the tablets if they were auctioned, Parsi’s typically measured interview voice became troubled:

“When you have a lot of artifacts--as we see in this case--the relative market value of each item drops. And as has happened before, the business owners destroy many of the items in order to increase the value of the remaining ones. We have seen this happen with Egyptian artifacts in the past. There’s a significant risk. It may actually happen that there will be a deliberate effort to destroy the stocks to make sure that the remaining 500 out of the 12000 fetch the best price! Then this part of our history and heritage will be destroyed.”

This is simply barbarism, committed in the name of 21st century justice. From a perfectly reasonable angle these tablets are just as important as the Darius Behistun inscriptions or even the Cyrus Cylinder. Why? Because archeological sites and museums are full of self-descriptions by rulers of what kick-ass heroes they were and how justly they ruled. Bein e khodemoon, “Cyrus Cylinder” kings were a dime a dozen. Even today, Kayhan is a daily Cyrus Cylinder made out of paper. To give substance to our past we need more than the words of Cyrus and Darius; we need to audit their receipts. And this is precisely what these tablets are: receipts, invoices, pay stubs, wage tables, reimbursement, how much food and wine the priests of different religions got to offer their gods, etc. sampling several periods of Achaemenid rule. So far the tablets reveal an empire buzzing with a complex economy, an active society and run by an intricately structured administrative system. There’s an astonishing amount of detail about Achaemenid life in these tablets, beyond what we could have reasonably hoped; their discovery is a cultural windfall for Iranians. Ironically if it hadn’t been for another barbaric act—Alexander’s--more than two millennia ago, these tablets may have been scattered centuries ago. The quick collapse of the Persepolis building hid the tablets and made them inaccessible...